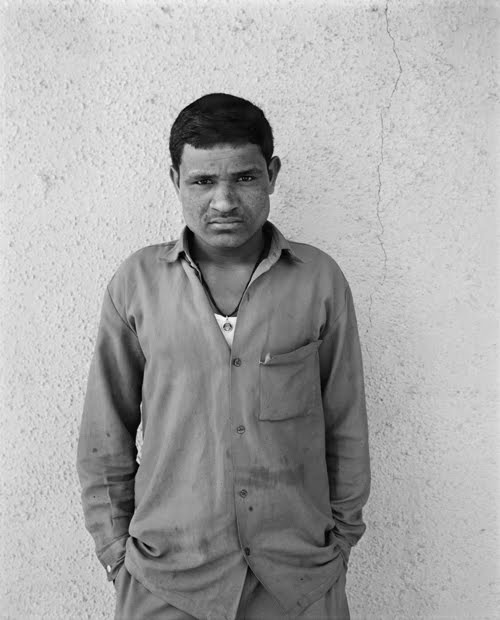

The photography of Ram Rahman can easily be said to fall predominantly into two categories: portraits and urban landscapes. Of the portraits, both posed and spontaneous, surely the more prominent are those of artists, socialites and politicians. This is not surprising as Ram was raised within a milieu where culture and politics mixed freely in the drawing rooms of New Delhi. In fact, the intersection of conversational hand gestures, floor cushions and glasses of Scotch is another of his most re-visited subjects. Yet it is the casually posed portraits of artist friends and acquaintances that prove Ram’s mettle, his adroit use of mise-en-scene to evoke the unique qualities of his subjects his forte.

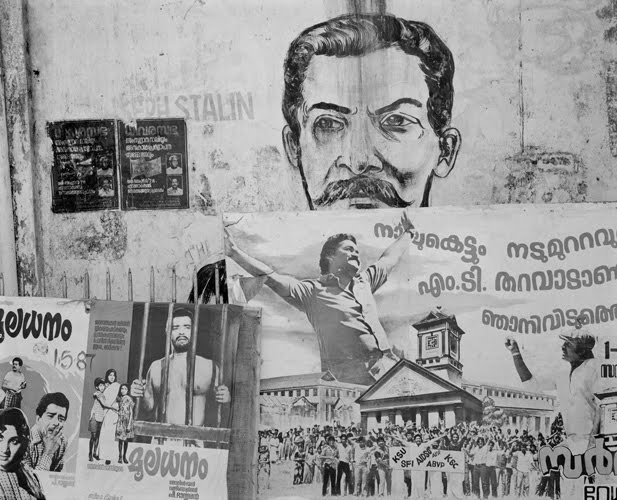

Ram’s camera has come to acknowledge a particular image of India’s cities, and particularly Delhi. The strange (but not surreal) confluence of people, architecture, signage and activity that one finds in urban India fits easily into Ram’s viewfinder, while his compositional style savors the flattening, foreshortening and collapsing of perspectives that happens readily in the black-and-white print. Ram delights in the subtle absurdities to be found in these juxtapositions, exploiting the opportunity to discover something about what might make Indians tick. Raised and still based in New Delhi, India’s capital and political engine, Ram has a special interest in the symbols of politics as they enter popular culture, the highly visual markers of both parties and players that get mixed into the cacophony of the streets, revealing playful readings of the public Indian psyche.

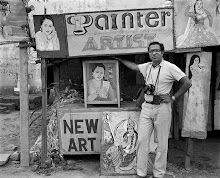

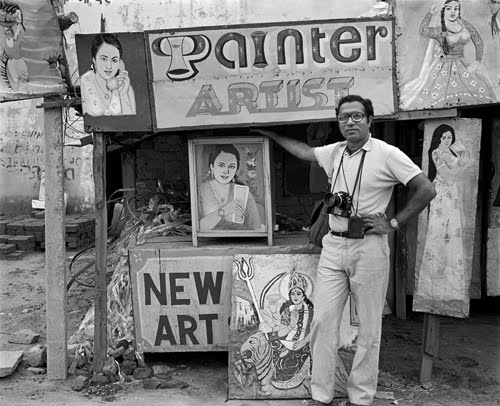

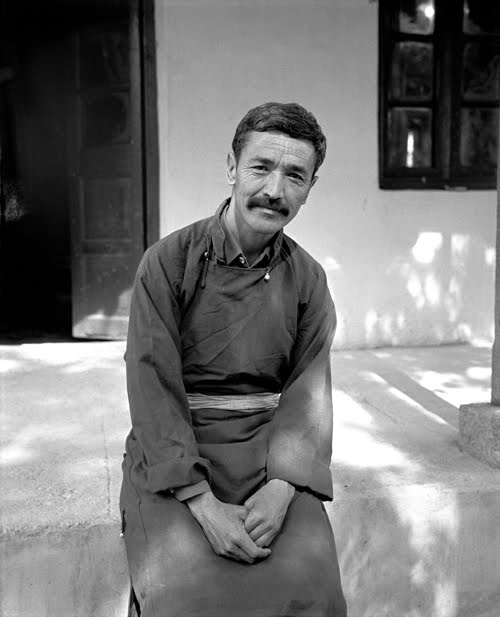

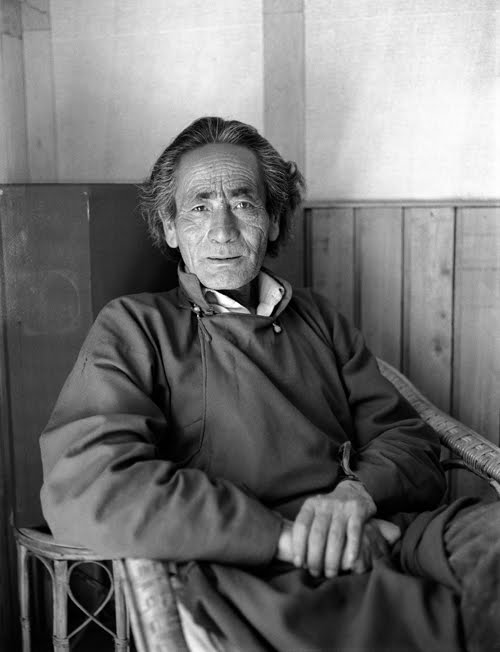

Two pictures bring together succinctly these two dominant strains in Ram’s work. In portraits of the photographer Raghubir Singh and the painter Bhupen Khakhar, Ram illustrates something of each man’s attitude towards his own artistic practice and something of what Ram has learned from both and incorporated into his own work. Both portraits of artistic mentors use public art as props and sets, weave irony with a slightly morose sense of humor, and rely on their subjects’ collaboration in constructing this rebus.

Singh’s portrait comes from a time before the photographic image dominated the facades of urban India, when the hand-painted poster and hoarding was the lingua franca of commerce. Singh’s slightly smirking expression acknowledges the in-between status of his own craft, where the making of a “New Art” will not be by the “Painter Artist” but by technological means, his equipment slung prominently from his neck. Khakhar’s portrait is more polemical, seating a father figure to many in the lap of the Father of the Nation. Khakhar, realizing the gravitas of the situation, doesn’t push his luck by camping it up (as he had been known to do on many occasions). Instead, he poses rather demurely, allowing a dramatic difference in scale and a contemplative glance to speak about personal battles, historical achievements, and the uses and abuses of patriarchies. Both portraits seem shot on-the-run, as if a spontaneous stop during a day of outings with friends, certainly not weighted by premeditation. With both, Ram achieves a characteristic balance of the playful with the somber, the visual with the thoughtful, and the deeply personal with the demandingly public.

Peter Nagy

No comments:

Post a Comment